Leon Narbey's Masterwork Considered

Leon’s master work is rescued and rises – a phoenix from the ashes. Waka Attewell considers meaning, art and what happens when our cinema history is bought and sold.

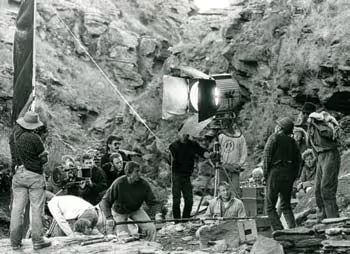

It’s the mark of a good movie when you’re still thinking about it a week later – it’s the mark of a great movie when you are still thinking about it after more than 20 years. When you can still recall the details… The cricket in the small box, the two Chinamen’s interior story of digging for an elusive fortune, their isolation, the sense of the advancing world, their previous life, surveyors scribing order into the wilderness, the camera that hung like poetry in the landscape. Leon Narbey’s Illustrious Energy (1987) is that movie.

I first saw Illustrious Energy on the big screen in the 80s when it was briefly released. It got me thinking ‘art’ and ‘history’ are an interesting combination. The outstanding beauty of it threw me for a moment and then I relaxed into the experience and let it wash through me. The unease I felt could have been because it was about us… about something dark in our past, but whatever it was there was simply something raw and compelling about its perfection. There are still moments etched on the back of my retina. It gave us fellow filmmakers permission to speak about craft without feeling like we had overstepped an invisible line.

If this movie is about ‘Art’ it’s also about something else – the nation in the throes of its birth, some of it ugly and some of it profound. It doesn’t need a car chase or an overly complex love story to make it cinema… try pitching this movie today. The most powerful moment of true love for me was when the old man, Kim, tries to remember his wife’s face after twenty-seven years abroad: 27 years of struggling with the land. Yet I found the Chan entanglement with the travelling circus at first distracting as it pulled me away from the interior. I now know why it’s there… Brilliant filmmaking. It was supposed to pull me to that place – there’s nothing random in play here.

Back then we all thought that filmmaking was important. We waxed lyrical about the edges of the frame, and spoke to the poetry of our work, we had invented a new language. We loved what we did and we loved the process. I asked **Chris Hampson **(the producer) how Leon had handled the edit and he mimed a person picking up a small object with his thumb and index finger and then turning the object whilst looking intently at both sides then putting it delicately down and picking up the next… He looked at me with a smile and said, “Every frame”.

But the word ‘unlucky’ springs to mind – Illustrious Energy never got a proper New Zealand release being one of eight titles dragged down when Mirage, the production company, suffered financial collapse. The receivers sold the lot offshore all boxed up and sent without ceremony.

We thought: maybe the master negatives had somehow found their way to the Film Archives? Maybe the Film Commission had kept the inter-negative, or copied the sound mixes? After all this is our cinema heritage, paid for by our taxes. But this was not the case. At the time we were aghast that not only the product of our craft could be bought and sold with such casualness, but that our cinema history was treated with such disdain. We had idealistically thought the rights of the Artist’s work were somehow sacred. The fact that film was just a mere commodity rocked our naïve belief that what we were doing was somehow important and everlasting – the truth was that movies were just another ‘horse trade’.

After changing hands several times, the film package was once again the property of a failed foreign company. Under these circumstances films go missing. However years later, and by a fortunate happenchance, Narbey, in London, heard that there might be some of the old Mirage titles in an old laboratory in Slough (yep the same of The Office fame). The re-titled ‘Dreams of Home’ (done without consultation, and a title Narbey hated) helped him trace the paperwork. He paid the lab a visit and there it was, along with some of the other lost Mirage titles, his masterpiece.

The generosity of the New Zealand Film Commission and Park Road Post enabled the achievement of Leon’s desire for retrieval, re-mastering and re-release of the movie. The original Cinematographer, Al Locke, was included in the grading (along with freelance colourist/grader Claire Burlinson). New Zealand cinema is all the better for Narbey’s continuing passion and commitment.

On its subsequence re-release the Otago Daily Times’ Shane Gilchrist called it the ‘finest film no-one has seen’. If the recent reviews are anything to go by he is not alone in his assertion. I recall a film-making colleague at the time of the film’s first short release summing up the feeling, “We’ll still be watching this movie 40 years from now, while others will just disappear into the ether.”

The new master was achieved from inter-positive (apparently it would have been far too expensive to go back to the original negative)… but the final results are spectacular.

There’s a time in the history of the New Zealand cinema that I remember with great fondness. I see the dividing line with precise clarity: the time before Robert McKee – and the ensuing script development hell, imposed upon the movie development process – and the time after. Not all of the angst was due to funding bodies, I might add, some angst was definitely self-inflicted as we tried to fulfil both the concepts of ‘art-as-cinema’ and ‘cinema-as-art’. Illustrious falls very much into the ‘before’ phase.

Personally I blame this artistic bent from the years sitting at the feet of Barry Barclay (RIP) and sharing the warmth from his particular fire. The film-making experience was more like poetry than the exploration of any formal scripting structure or the least like shooting a six-week schedule… he always made room to evolve the concepts… he found what he wanted through paintings, sketches, diaries, poems, flowing lines – these days they call this concept ‘organic’ or ‘experimental’. Back then we just called it film-making.

This Indigenous film-making (from within the culture) was also somehow perceived as slightly unorthodox, yet Leon Narbey and Martin Edmond also seem to have bridged a gap here… this is not a colonial story where the Chinese are observed… we are in the interior of the story and the colonial world intrudes.

It’s a special New Zealand iconic movie for that reason alone.